A central bank is not only the government’s bank but also a primary financial regulator. The institution takes charge of monetary policy, a tool that it deploys to regulate the pace of economic growth. There exists within the central bank various committees, each with a particular task. The most important committee, as far as monetary policy is concerned, is the open market committee.

In the United States, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has eight scheduled meetings in a year during which the members make critical decisions to economic growth. Among other things, FOMC meets to set target interest rates (also called Federal funds rate); they can raise the target rates, decrease, or leave them unchanged.

The federal funds rate is the threshold at which commercial banks extend overnight debt to each other. This is the same rate at which the Federal Reserve lends to commercial banks in overnight loans.

The significance of the federal funds rate manifests itself in the extent to which it influences both consumers and producers. The rates have knock-on effects on the cost of credit, and financial products, such as personal loans and mortgages, term deposits, and savings accounts.

Why do interest rates change?

FOMC meets regularly (usually eight times a year) to deliberate on the economic situation. Part of the deliberations includes determining whether adjusting the target interest rates (federal funds rate) can shift the economy in the desired direction. The committee achieves this goal by adjusting the target interest rate accordingly. Top on the priority list is to ensure that the US dollar is stable, stable inflation, and full employment.

You might be asking yourself, what motivates FOMC to change interest rates? Interest rates change regularly in response to certain economic indicators. But why do they change?

Shifts in demand and supply

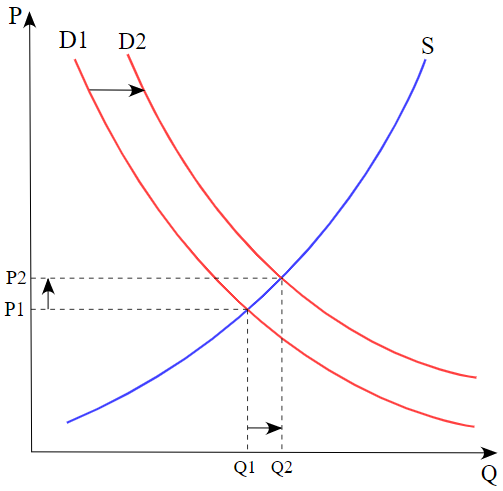

Money is the lifeblood of economic activity. People need money to exchange value. The higher the economic activity, the higher the velocity of money flow. When the demand for money spikes and supply remains the same, the price increases from P1 to P2 (as shown in the figure below). The price of money is another term for interest rates. At quantity Q1, the interest rate in the economy is P1, but this rises to P2 after quantity demanded shifts to Q2 along the supply curve.

Shifts in demand for money happen when output levels in the economy increase. Higher output puts more money in consumers’ pockets, and producers hire more workers to sustain the output levels.

Price growth (inflation)

The higher economic output often carries prices with it. For this reason, lenders charge interest rates on loans with one eye on the future price levels. If a lender determines that future inflation will be higher, the lender will charge higher interest on a loan to avoid making a loss.

For example, the United States, under Richard Nixon, uncoupled the greenback from the gold standard to stimulate inflation and cut down unemployment. The resulting loose monetary policy shot inflation up to 10% between 1974 and 1981.

Afterward, the Fed scrambled to increase target interest rates (from 5% in 1976 to 13% in 1980) by selling government debt. The aim was to reduce the money supply to avoid hyperinflation.

Government through fiscal policy

While the central bank is in charge of monetary policy, another government agency controls what is called fiscal policy. Fiscal policy is a tool that the government uses to regulate the aggregate supply and aggregate demand within an economy. It includes cutting/raising taxes and increasing/decreasing government expenditure. Through fiscal policy, the government can influence inflation and, by extension, a change in interest rates.

How interest rate cuts affect the well-being of consumers

The term well-being refers to the state of being happy and content. From an economic perspective, well-being refers to consumer satisfaction with the utility derived from the consumption of economic goods and services. The most satisfied consumer is the one with the most addressed needs.

As we have seen, central banks mostly raise interest rates in response to ballooning inflation. Inflation is always a bad thing from the consumer’s standpoint. It means one has to pay more for a product/service that was cheap just the other day. But does this mean interest cuts are always fair to consumer well-being?

Cheap credit

When a central bank, such as the Fed, cuts interest rates, it means the costs banks pay to access capital (in terms of reserves from the central bank or other commercial banks) is low. The banks then extend the courtesy to consumers by lowering the interest that they charge on loans. Cheaper loans allow consumers to borrow more to meet as many needs as possible, hence improving their well-being.

Returns from savings account fall

Bank deposits are a critical source of capital for financial institutions. When target interest rates are high, banks borrow less and turn to encourage more people to save with them. Of course, the banks have to set attractive interest rates on the savings accounts to attract as many people as possible.

Interest rate cuts open an opportunity for banks to obtain capital elsewhere and at lower rates. It means they will also lower the rates paid on savings accounts, which ends up discouraging savers. Fewer saving opportunities deny consumers avenues to grow their income, which ends up deteriorating their well-being.

Rate cuts have mixed effects on investments

Some investments, such as stocks, react positively to lower target interest rates. As earlier explained, lower rates cheapen credit and increase money flow. It means more people will have more money to put into risky assets such as stocks while avoiding bonds. If you own some shares, the period of lower interest rates is perfect for selling at a premium because of higher demand. However, bond investors might suffer losses due to falling yields.

The bottom line

Interest rates are critical to the well-being of consumers. Central banks use the target interest rates as a tool to regulate the flow of money and stabilize rates of price growth. Although low-interest rates increase consumer well-being, some consumers suffer eroded comfort when their savings accounts earn low interest.