Quantitative Easing, or QE for short, has become a popular term, having featured prominently in the last major economic crises, the most recent being in 2020.

During each period, the global economy escaped hyperinflation. For 2020, the global economy was in an unprecedented situation that discouraged inflation even with excess money flow.

Defining and explaining quantitative easing

Quantitative Easing is a monetary policy tool that central banks apply to jumpstart an economy after (or during) a recession. QE is like shock therapy that an unresponsive patient receives to bring them back to life. Central banks often fall back on QE when any other tool cannot work. What happens is a central bank prints money and uses it to buy debt from the private sector – usually bonds from commercial banks. The banks then pass on this money into consumers’ pockets via credit facilities.

Monetary policy is the mechanism that central banks use to control the money supply in an economy. Central banks have a set of tools – such as rate cut/raise, Open Market Operations, etc. – that they deploy to achieve their aims. These are conventional tools.

When the economy is unresponsive in the face of the full force of conventional monetary policy, central banks are at liberty to deploy unconventional monetary policy tools such as QE.

Does QE automatically lead to hyperinflation?

Inflation is a hot topic in developed economies, especially after central banks failed to stimulate higher prices for a long time. The supply side of the economy depends on inflation to increase production, and hence profits. If inflation is moderate and in tandem with salaries and wages growth, consumers will continue to participate in the economy.

Sometimes, inflation overblows, and consumers cannot afford to buy anything because of a badly devalued currency. This situation is called hyperinflation. Different economists have different thresholds for when inflation becomes hyperinflation. Typically, inflation levels above 50% imply hyperinflation.

Hyperinflation is not common, but it happens when prices rise rapidly and in a sustained manner. The rapid rise in prices often emanates from an oversupply of paper money. Herein lies the connection between hyperinflation and QE.

Since QE entails the pumping of large quantities of fiat money into an economy, the logic is that this excess supply will make prices rise rapidly and sustainably hence leading to too much inflation.

Consumers are always on the receiving end of hyperinflation. Some economists describe this phenomenon as taxation on consumers. Say you have $10,000 in cash in your possession today. If the monthly inflation rate is 50% (hyperinflation), then your cash will lose half of its value every month.

QE: An example of how it works

Let us consider a simplistic illustration of QE. Consider the balance below of GNE Bank, a US-based commercial bank. The table shows that GNE Bank has $600 million in assets (comprising loans, bonds, and reserves) and liabilities worth $550 million. It means GNE Bank’s net worth is $50 million (assets – liabilities).

| Assets | Liabilities and Net Worth | ||

| Reserves | 60 | Deposits | 550 |

| Loans | 240 | Net Worth | 50 |

| Bonds | 300 | ||

| Total | 600 | 600 |

Figure 1: GNE Bank’s original balance sheet

Faced with a menacing recession, the Fed launches a QE program, and it targets the purchasing of bonds from commercial banks. The Fed purchases bonds worth $100 million from GNE Bank. But GNE Bank is not interested in increasing its reserves and instead opts to loan out the new funds. Now, GNE Bank’s balance sheet looks like Figure 2 below:

| Assets | Liabilities and Net Worth | ||

| Reserves | 60 | Deposits | 550 |

| Loans | 240 + 100 = 340 | Net Worth | 50 |

| Bonds | 300 – 100 = 200 | ||

| Total | 600 | 600 |

Figure 2: GNE Bank’s new balance sheet after the Fed’s QE goes live.

GNE Bank’s new loans have now increased the money supply in the US economy. Therefore, the Fed’s actions have resulted in more money flowing into people’s pockets and producers’ bank accounts. As a result, aggregate demand in the economy will rise, and with it the prices of goods and services. If the Fed aimed to stimulate inflation, then it has just hit the target.

Why did the latest QE not cause hyperinflation?

Evidence from the past decade – and as recent as 2020 – shows that QE is not always hyperinflationary. However, the economic situation during the COVID-19 pandemic was special in a way that no amount of QE could lead to overblown inflation.

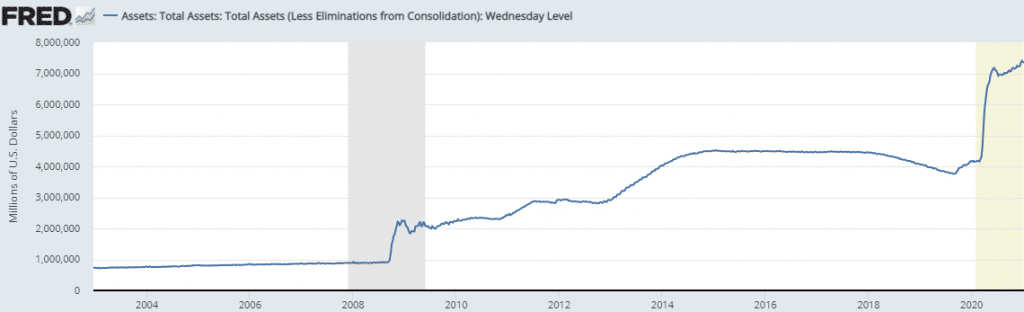

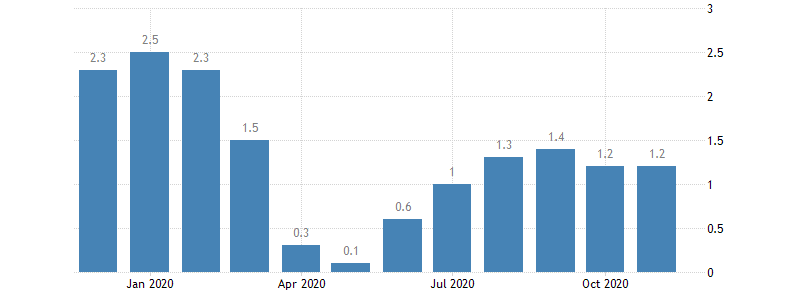

The US Fed grew its balance sheet within the first six months of 2020 by the same magnitude as it did between 2002 and October 2013. By November 2020, US inflation was 1.2%. The lowest point that inflation touched for the year was 0.1% in May, and the highest was 2.5% in January (before the Fed’s massive bond-buying program started).

Two scenarios can explain the anomaly. Firstly, most of the Fed’s money into the economy did not make its way into the real economy. Largely, the government was paying people to stay indoors to stem the spread of the coronavirus COVID-19. The incentive to spend the money was, therefore, absent. Without the money vying for products, there was no stimulation for prices to rise.

The second scenario was that the supply side of the economy was in disarray. Many workers staying indoors meant that production cuts were the order of the day for lack of labor. The demand-side and supply-side problems then converged to suppress any chances of hyperinflation in the US and elsewhere, where governments rolled QE programs.

Conclusion

Few economies have undergone hyperinflation, and most of these happened during periods of war. Others, like Zimbabwe and Venezuela, have resulted from corruption, economic sanctions, and poor monetary policies. Since the Great Recession, QE has become an important tool in the central banks’ arsenal.

Although QE does not automatically cause hyperinflation, evidence shows that a badly timed ending of QE could lead to a hard landing – a situation where the economy is thrown into crisis because of a sudden stop of money flow.